A sense of mystery: that is what was missing. Once upon a time, back in the distant dark ages, it was possible to own records about which nothing was known outside of what was printed on the jacket and label. So much of what counted as knowledge back then was based on half-truth, rumour, legend and lies. Nothing could be certain. Our imaginations filled in the rest. Then came dial-up, and all that changed. By the turn of the millennium our ignorance had evaporated in the face of information technology’s relentless forward march: all of the gaps were being filled in. What place for obscurity, for mystery, in the Wikipedia age, when everything is instantly knowable? Whether we were cognisant of it or not, the desire lingered on.

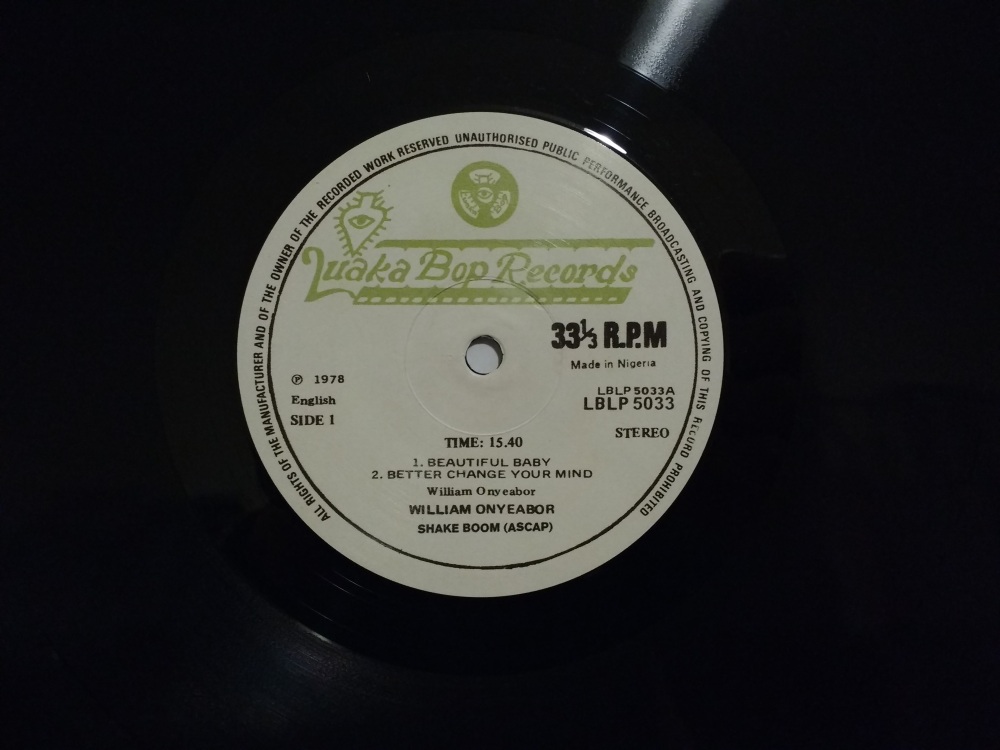

In 2001, the year of Wikipedia’s launch, Quinton Scott and Duncan Brooker from UK based reissue label Strut released the first of their seminal Nigeria 70! compilations. Among its treasure trove of obscure afrobeat gems, one track – a long, trippy groove called ‘Better Change Your Mind’ – stood out, for its unexpected inclusion of primitive machine percussion, its layered synthesiser riffs, its infectious, squelchy rhythms, and the warm, beguiling voice, gently but firmly admonishing the great powers of the Cold War for acting like they owned the world. It was lo-fi. It was funky. It was deeply strange. It was, in many ways, the highlight of the compilation. Everybody who heard it, even those who thought they knew a thing or two about West African funk, agreed it was quite unlike anything they had heard before.

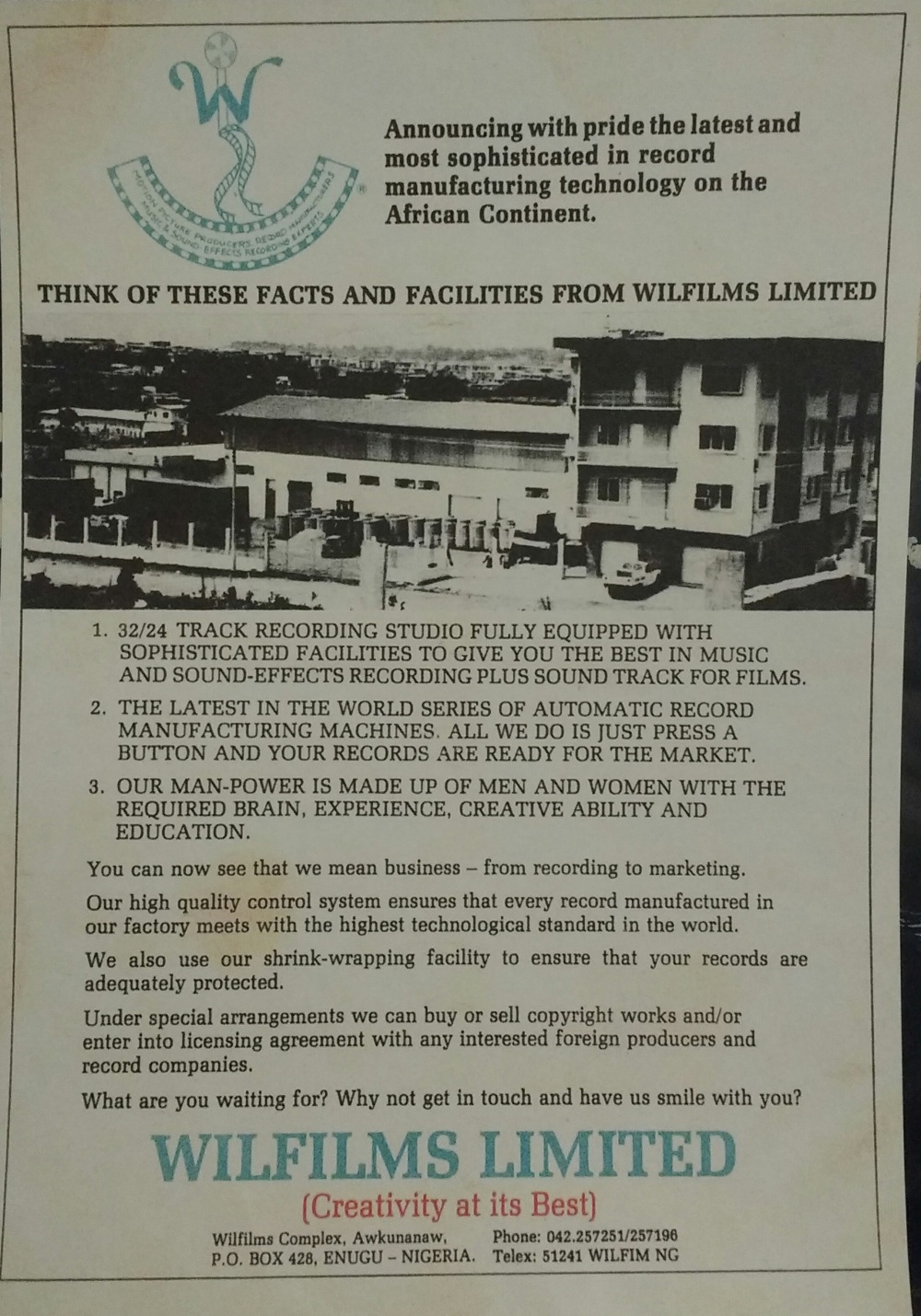

About the owner of the voice, and the creator of this oddly compelling fusion, scant facts were known: William Onyeabor was born in Enugu, Nigeria; he studied film production in Russia; on his return to Nigeria he created a company, Wilfilms Limited, and made a movie, Crashes In Love (“A tragedy of how an African Princess rejects the love that money buys”); when the soundtrack proved more successful than the film, he dedicated himself to music-making; between the years 1977 to 1985 he recorded and self-released eight impossible-to-find albums of pioneering electronic afrobeat, all of which Onyeabor made at his own studio and record-pressing plant; after 1985’s Anything You Sow, he abandoned music, became a born again Christian, and dedicated himself to Jesus.

These tantalising outlines of a biography, raising more questions than they answered, were never going to satisfy the curiosity awakened by ‘Better Change Your Mind’. One of those who found William Onyeabor an itch impossible not to scratch was Nigerian-born, Boston-based writer Uchenna Ikonne, who runs the African music blog Comb and Razor. In 2009 he had secured, by telephone, Onyeabor’s verbal agreement to release a compilation of his music. All that remained was to secure some funding for the trip to Nigeria, and to get Onyeabor to sign on the dotted line. He contacted Yale Evelev, president of Luaka Bop, who had also used ‘Better Change Your Mind’ on their own World Psychedelic Classics, Vol. 3: Love’s A Real Thing: The Funky Fuzzy Sounds of West Africa. Evelev agreed to put up the necessary finance.

Mr. Ikonne flew to Nigeria expecting to have everything thrashed out in three months. Negotiations took, in the end, three years. Even then, Ikonne and Luaka Bop could come up with next to no useful information about the man. Many artists who achieve cult recognition in later life are only too happy to bathe in their newfound recognition. Onyeabor was having none of it. What they encountered was a man impossible to deal with: someone who refused, point blank, to discuss himself, his past and, especially, his music. All he wanted to talk about was Jesus.

What was clear was that Onyeabor was a big man in his local community. He had been given the title of high chieftain, had been made an honorific justice of the peace, was a pastor, and even had a street named after him. Locals offered up plenty of legends and rumours, but little in the way of verifiable fact. Some even seemed afraid of talking about the reclusive figure in their midst. Try as they might, neither Iknonne nor Evelev could uncover a solid basis for Onyeabor and his story. “He didn’t threaten me with violence,” recalled Ikonne, “but he broke me, he really broke me. Up until that time that was the toughest ordeal I had ever endured in my life, just dealing with him. I don’t think I could listen to his music for maybe two years after that”.

In 2013 Luaka Bop decided to put the compilation out anyway, despite the dearth of critical information about its impenetrable subject, only its title was to be changed from This is William Onyeabor to Who is William Onyeabor? This was followed by remixes, a series of tribute concerts, and a documentary. In 2014 came the holy grail for collectors: the complete albums. For the vinyl edition the albums were split among two numbered, limited-edition clamshell boxes that came with booklets, a poster and 7-inch singles.

They are beautifully packaged, with striking graphic design, and reproduction sleeves and labels suitably weathered by artificial ageing. The albums were mastered by Joe Lambert, with incredible transfer work from disparate sources by See Why Audio’s Colin Young. The vinyl is quiet and sounds lovely. Both boxes were gifts from my brother, who alerted me to Onyeabor’s strange and enchanting music. As objects they are a joy to own, and no comparable act of musical generosity has given me such boundless listening pleasure over the last few years.

William Onyeabor’s music is unique: a fusion of afrobeat and electronics that has no obvious precedent. His later albums, in particular, seem bizarrely ahead of their time, their synthesiser pulses and sequenced architecture suggesting nothing less than a Nigerian Kraftwerk, or a West African Giorgio Moroder. As many a house music DJ would attest, their stomping beats and big hooks don’t sound out of place on contemporary dance floors.

In contrast to the difficult, formidable refusenik he proved to be in person, Onyeabor’s music radiates warmth and openness. It is constantly surprising, full of synthesised eccentricities and lyrics of self-aggrandising wit. Even when touching on subjects like civil war, corrupt dictatorships and nuclear war, this is essentially a joyous, optimistic vision. Unlike the fiery workouts of fellow countryman Fela Kuti, Onyeabor’s groove is intimate, laid back, almost introspective; his music animated by a keen intelligence, quiet wisdom, and an innocent, almost childlike, sense of moment-by-moment musical discovery.

That Onyeabor was doing all this pioneering experimental work completely self-sufficiently, in almost total isolation from even the Nigerian music industry, boggles the mind. He seems blithely unaware that he isn’t a superstar outside of his own vinyl grooves, where he is the ‘Great Lover’ and the ‘Fantastic Man’, and on the unforgettable covers, where he can be seen showing off, peacock-like, both his vast battery of synthesisers and microphones, and a fetching array of dramatic suits and strange hats.

William Onyeabor’s albums have been on heavy rotation since I learnt (on my 40th birthday) of his death, at the age of 70. He died on the 16th of January, at his compound in Enugu, following a short illness. Onyeabor’s passing is a poignant moment, both because he bought such uplifting and life-affirming music into the world, and because he takes so many secrets with him into the silence of the grave.

An enigma to the end, most of the important questions remain unanswered: What was the true nature of his relationship with Soviet Russia? Where did his money come from? Does the film Crashes In Love really exist? How did he learn to make music? Who were his influences? Where did he get all those synthesisers, which were by no means easy to come by in 70s and 80s Nigeria? How did he learn to play them? Why did he never, as far as we know, perform his music in public?

“I really struggled with putting out an album without any facts or commentary from someone about how this music came to be. It just seemed shoddy,” says Luaka Bop’s Yale Evelev, “However when we realized the same few sentences of information were posted everywhere there was any information about him, we thought, what an incredible thing in this day of hyper information to find someone, who though he is alive, is known in his community, has innumerous businesses, had put out eight albums, had his own label, film studio, pressing plant (and who knows what else), is somewhat of a blank slate of information”.

Farewell, then, Fantastic Man. A true one-off, whose music makes this listener very happy indeed.